Taiwan Lit and the Global Sinosphere

Translating Ling Yu’s Poetry: Workshop at Looren, Switzerland, 2024

* The report was originally published on the author’s personal blog and has been reposted with her permission. For the full translations of Ling Yu’s poetry from the workshop, please refer to the final section of the report.

When I stayed for two weeks at the Translators’ House Looren in March 2023, I heard that they regularly held workshops, but I didn’t ask for any details, assuming they would not be about Chinese literature anyway. Feeling very inspired by my visit, I straightforwardly inquired with the Looren administration about organizing a workshop on the translation of Taiwanese poetry myself. I had no idea that their workshops were usually organized with other partners (such as schools) and included all meals for participants, provided by the Translation House—significantly increasing the total costs. So, I proposed that we cook for ourselves, drew up a program, and, whereas the workshops usually involve only two languages (the source language and the target language), I suggested translating from Chinese into several European languages. Despite this unconventional approach, the administration welcomed us, and I carried on with organizing the workshop.

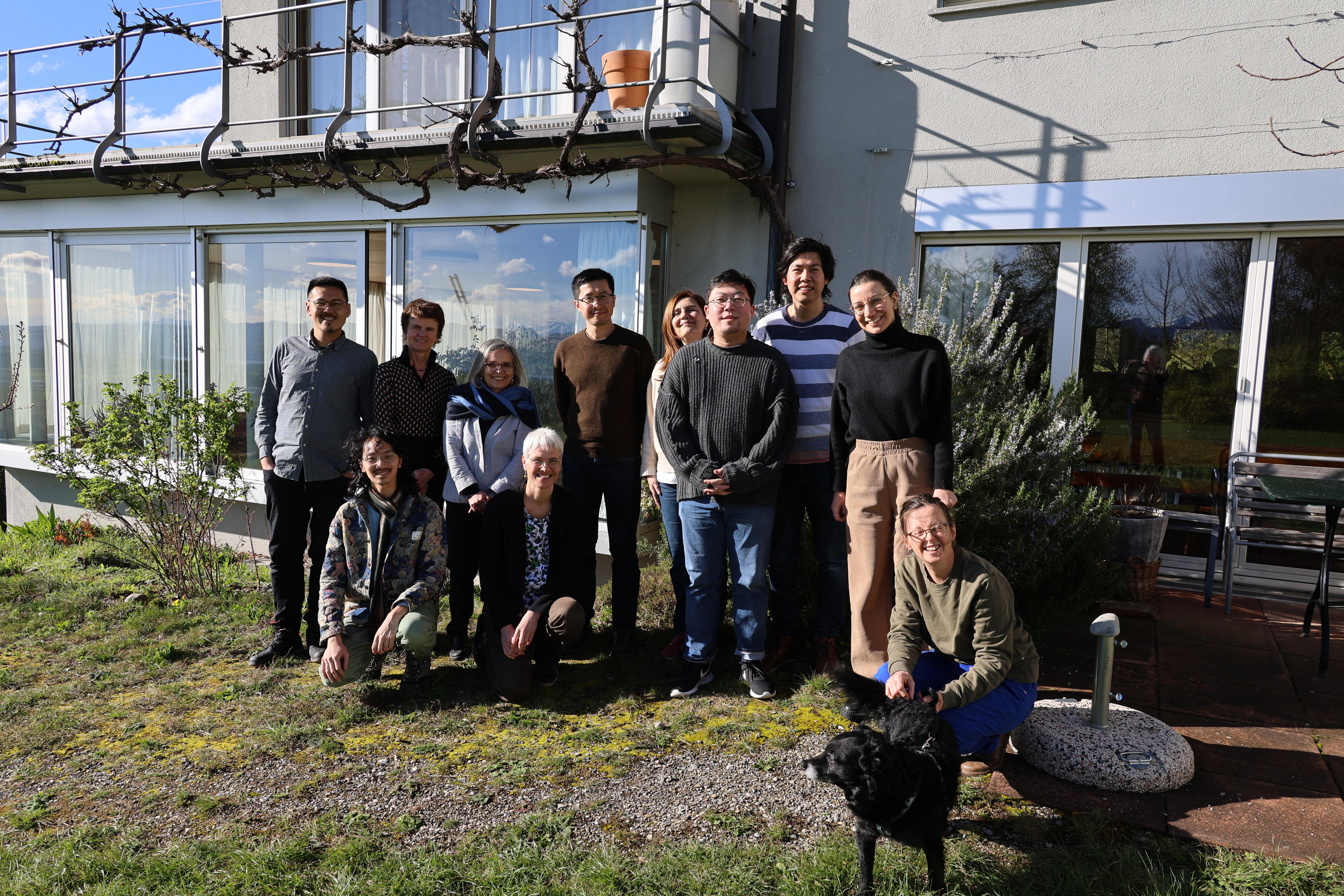

As I enjoy translating poetry, I suggested to several translators in Europe that we organize a practical translation workshop focused on the poetry of Ling Yu from Taiwan, whose work I was translating myself. Ling Yu is a renowned poet in Taiwan and had just won a significant prize in 2022 for her latest collection, Daughters (女兒). I knew that Nicholas Y. H. Wong (University of Hong Kong) was translating this book into English, that a French edition of a selection of her poetry had recently been published, and that in Switzerland, Alice Grünfelder was also deeply interested in her work. Unfortunately, the French translator could not participate, but three Italian translators—Rosa Lombardi (Roma Tre University), Silvia Schiavi (Roma Tre University), and Cosima Bruno (SOAS, University of London) — joined us, along with Dylan Wang (SOAS), a native speaker of Chinese based in London, and Tony Yu (National Taiwan Normal University), Yu-sheng Tsou (University of Munich), and Wen-chi Li (University of Oxford) from Taiwan. I should note that the native speakers in the workshop all had an excellent, near-native proficiency in their second language (English or German).

I had considered inviting the poet herself to the workshop, as I often collaborate with poets whose works I translate, asking questions about the meaning of words or sentence structures that might be unclear to me. Sometimes, they also clarify allusions. On the other hand, some translators explicitly prefer not to contact the poet, wanting the freedom to create their own interpretation. Ultimately, I decided against inviting her. Besides, we had a few native speakers in the workshop, which may have been more useful, as it highlighted how different native speakers read and interpret a text.

We all had different reasons for joining. Most participants work in universities as PhDs, teachers, or professors of literature, translation studies, or philosophy. They translate literature or poetry occasionally, driven by personal interest or as part of their teaching and research. Some also write poetry themselves, while others are more focused on language, have a philosophical background, or approach literature from historical or social perspectives. I was the only independent freelance translator in the group. What I miss most as a translator working from Chinese into Dutch, after years of solitary work from home, are discussions with colleagues. There are only a few people working on Chinese-language literature in the Netherlands, and we rarely meet, especially since I live in France. The group that came together at Looren turned out to be a perfect mix for exchanging ideas.

Many of us didn’t know each other personally. We arrived over the weekend and got acquainted during our first get-together dinner on Sunday, kindly hosted by Alice. Luckily, I must add, as it had completely escaped my notice that shops in the area were closed on Sundays! Our organization of meals for the rest of the week—some more Italian, some more Asian—proceeded much like the workshops themselves: efficient yet relaxed, always interesting, and wonderfully convivial.

Before the workshop began, I had asked all participants to select one or two poems by Ling Yu. We shared these Chinese poems along with our first draft translations in advance, with everyone translating into their own language, including English, Italian, German, and Dutch. This allowed us all to prepare for the discussions ahead. During the workshop, each participant led a half-day session, presenting the specific challenges of the poem they had chosen.

So, who is Ling Yu, and what is her poetry like?

Ling Yu’s Life and Poems

Ling Yu (Taipei, 1952) earned a BA in Chinese Literature at the National University of Taiwan and an MA from the Department of East Asian Languages and Literature at the University of Wisconsin. She has worked as an editor for the book supplement of the Taiwan Times (台灣時報), served as a visiting professor at Harvard University from 1991 to 1992, and taught at Yilan National University from 1992 until her retirement in 2021. Additionally, she was an editor for the poetry journal Modern Poetry (現代詩), a co-founder and editor of the pioneering journal Poetry Now (現在詩, alongside Hsia Yu 夏宇 and others), and deputy editor-in-chief of The World of Chinese Language and Literature (國文天地雜誌社). She has received several major literary awards in Taiwan and has been invited to numerous international poetry festivals.

Ling Yu’s idiosyncratic poetry draws heavily on history, art, philosophy, and mythology. In addition to influences from Taiwanese, Chinese, and Japanese culture, her work often references Western classics. Her poetry can be as surprising as Li Bai, as melancholic as Du Fu, or as intricate as Li Houzhou. Like Tao Yuanming, her poems express a love for simplicity, detached from the bustling rhythm of cities and politics. Her work also references diverse painters, including the Chinese Bada Shanren (eighteenth century), the American Georgia O’Keeffe (twentieth century), and the Mexican Frida Kahlo. Zhuang Zi, whose work she considers a pinnacle of East Asian aesthetics, seems a big source of inspiration. In her own poetry too, Ling Yu emerges as someone who loves contradictions and paradoxes: Themes of light versus dark, day versus night, freedom versus captivity, the hermit versus society, and rock versus water often emerge, as illustrated in lines like:

“I want to dream but not sleep / I want to walk but without feet.”

As observed during the workshop, Ling Yu’s style is calm and contemplative, with an elegant, natural cadence. Her work eschews obvious rhyme, meter, or linguistic play, instead focusing on pure and distilled expressions of emotion and insight. She uses few adjectives and adverbs, emphasizing clarity and restraint. Her sensitive, modest voice often carries a Zen Buddhist undertone. Original metaphors and serial forms distinguish her work. She may well be the poet who has written the most “serial poems” (組詩) in Taiwan, and possibly in the entire Chinese-speaking world.

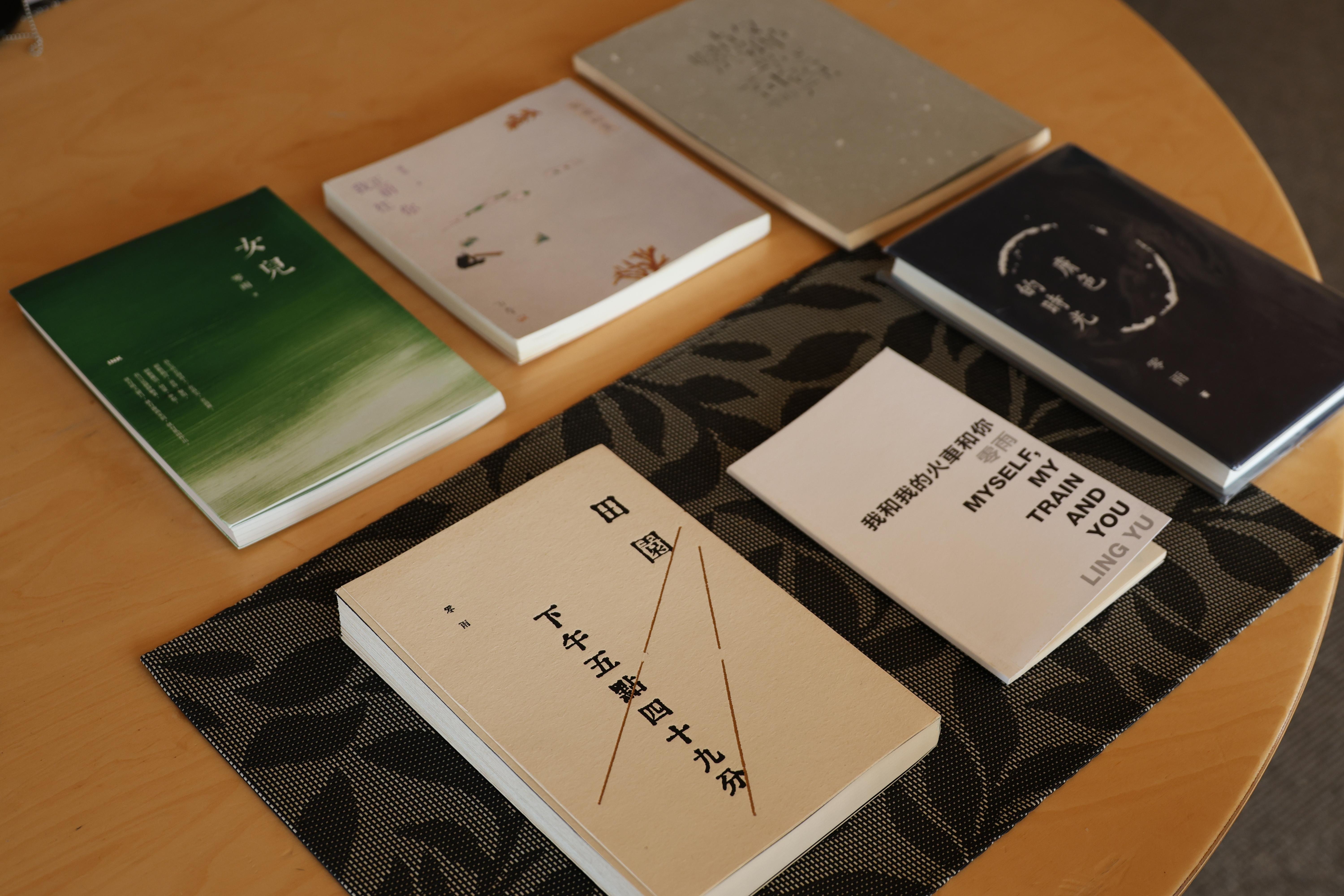

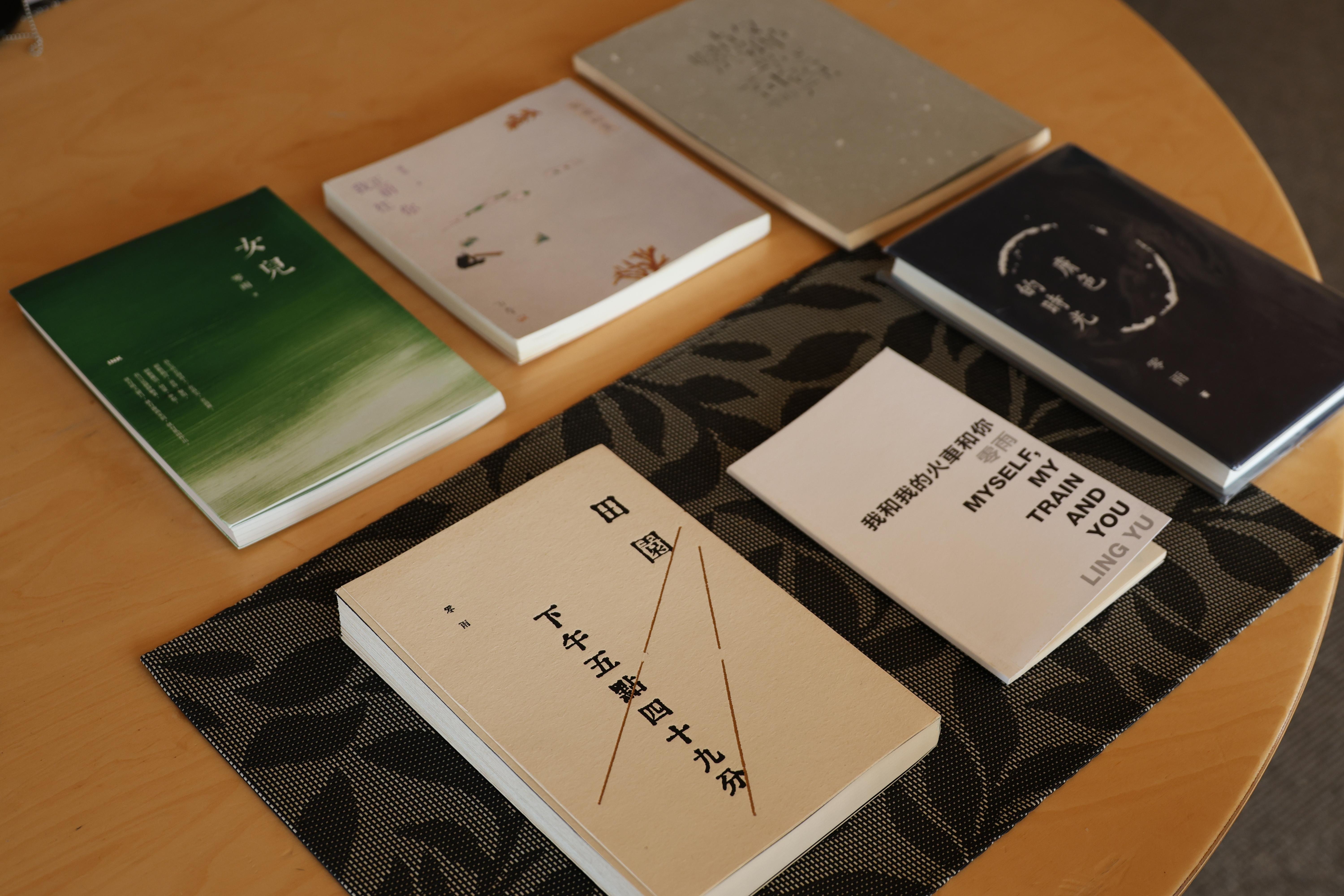

Since her debut in 1988, Ling Yu has published nine poetry collections, each with a distinct focus. Recurring themes include female emancipation, the destructive impact of capitalism on nature and human life, train travel, the classics, and landscapes. For the workshop, we primarily translated poems from her two most recent collections: The Era of Skin Color (膚色的時光, 2018) and Daughters (女兒, 2022). The former delves into Chinese tradition, while the latter responds to the illness and death of her mother. Daughters explores the roles of daughter, mother, and woman—both as an individual and in familial and social contexts. Additionally, the collection serves as a tribute to the Japanese artist Ando Hiroshige (1797–1858, also known as Utagawa Hiroshige or Andō Tokutarō), whom Ling Yu regards as a symbolic maternal figure. Both “mothers,” she says, have accompanied her throughout her life.

Difficulties in Translation

Part of our time was spent on defining the style, the textual references, and the exact meaning, function, or effect of the Chinese words, to find the accurate words in our respective languages. Some translation problems are not limited to Ling Yu, but are true for translating Chinese into European languages in general. Well-known examples are the choice of whether to use capitals (non-existent in Chinese); the lack of verb conjugations in Chinese (the perception of time is different); significantly different sentence structures; the lack of singular and plural forms and of articles, as well as the lack of demonstrative and possessive pronouns where European languages require them.

Of course, the completely different use of punctuation is also an issue. For example, we struggled with Ling Yu’s frequent use of the dash, which, as we mostly agreed, cannot be used so abundantly in European languages. Additionally, we failed to see consistency in its use. Like most modern poems in Chinese, Ling Yu does not use punctuation at the end of a verse line, nor the full stop to mark the end of a sentence. Enjambments are quite commonly used, but many Chinese poets use them mostly to create tension or emphasis only. Ling Yu, however, regularly has inventive enjambments, using a combination of sentence structures and ambiguous words to create ambiguity in a meaningful way. For instance, in these lines from the 6th poem “Rocks” (岩石) of the series “My Name Is Sea” (我的名字叫海) in Daughters:

Ah, the young—

rocks finally

settle down

啊這些年少的——

岩石終於

定居下來

Here, the word “young” in the first line can be interpreted as a noun, referring to the younger ones, or as an adjective modifying “rocks” in the second line, meaning the young rocks. Or in these two lines from the poem “Exchange” (調換) in Daughters:

Her stomach already can no longer hold me

the food given to her

她的胃已經不能裝我

給他的食物

This whole stanza, when read as an enjambment, can easily be translated very straightforwardly as: “Her stomach can no longer hold the food I gave her.” But the meaning of the isolated first line, “Her stomach can no longer hold me,” also comes into play. This reading can be interpreted as: she is no longer able to deal with me—in other poems from the collection, it is clear that the mother is bedridden and can no longer communicate (see the poem below). The translator must be inventive to reproduce a similar ambiguity in the European language.

Sometimes, the different etymology of words seemed important to a translator. The first lines of the 7th poem in the series “Watching Paintings” (看畫)—based on Hiroshige’s The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō—provide a good example:

被時光燒成了灰燼的富士山

像一座紅色的海市蜃樓

These lines can be translated as:

The Fuji that has been burnt to ashes by time

seems to be a red mirage.

Literally, the Chinese phrase for fata morgana consists of the characters for see, city, marine monster, and storied buildings. In former times, people assumed that the breath exhaled by a monstrous marine animal created the illusion of cities or buildings in the air above the sea. In European languages, fata morgana was thought to be created by the witchcraft of the Italian fairy Morgane (from the King Arthur legends); however, what the visual illusions looked like is not made explicit. Since the storied buildings in the Chinese seem significant in the series, the translator wanted to find a way to retain them in the translation.

Yet another challenge came with the linguistically quite simple poem “木頭人,” which literally means “Wooden man” and is short for “一、二、三木頭人” (“one, two, three, wooden man”). This is the Chinese name for the children’s game that is known all over the world by different names. The English say “one, two, three, piano,” just like the Flemish; the French say un, deux, trois, soleil; the Germans call it eins, zwei, drei, Ochs am Berg; in Italian it is uno, due, tre... stella; and the Dutch have Annemaria koekoek. The popular (and horrible!) South Korean Squid Game is based on this game, but luckily, that has nothing to do with this poem.

The full Chinese poem goes as follows, with a literal translation:

“Wooden man” 〈木頭人〉

One two, three, wooden man 一、二、三木頭人

I and my childhood 我和我的小時候

playing this game 玩著這個遊戲

One two, three, wooden man 一、二、三木頭人

My mother—I play with her 我的母親──我和她玩

She lies in bed 她躺在床上

I and Wati together help her, sit 我和瓦蒂一起扶她,坐起來

lie, turn 躺下來,翻身

talking with her 和她說話

She does not reply 她不回答

She does not nod or shake her head 也不點頭搖頭

Fortunately, the eyes can move, can see me 還好眼睛會動,會看我

One, two, three, wooden man 一、二、三木頭人

This game is back 這個遊戲回來了

I and my childhood 我和我的小時候

Obviously, the wooden figure here has a richer meaning than just the game because the ill mother is like a wooden doll, unable to move. In the first stanza, Ling Yu again creates a meaningful enjambment in the second and third lines, which can be read as: “I and the game that I played in my childhood,” but the second line also stands by itself: “I and my childhood,” even more so because it is the last line of the poem as well. It seems important because it draws attention to the fact that the serious illness of the mother throws the “I” back into time, back into childhood. In the third stanza, the term Wati (瓦蒂) is interesting. Everyone familiar with Taiwan knows that there are many people from Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines who come to Taiwan to work in households. Wati is the name of such a person of Indonesian origin (Balinese, as Nicholas Y. H. Wong clarified). In other poems, we came across the generic term 外勞, meaning labor from outside Taiwan. This term is very short in Chinese, clear to everyone familiar with the language, but in European languages, it becomes longer, sometimes unnecessarily so, and may even arouse unwelcome associations with discrimination.

Another interesting aspect of the workshop was seeing which poems everyone selected. It seems to me that native Chinese speakers generally had fewer difficulties selecting poems strongly grounded in Chinese (or Asian) traditions, as the titles often indicate, such as “Du Fu, 767” (杜甫(公元767年)), “Dreaming of Classical Chinese” (夢見文言文),”Pine Snow Studio: To Huang Gongwang” (松雪齋:致黃公望), or the series “Watching Paintings,” dedicated to Hiroshige. Personally, I often hesitate to select and translate poems I fear are “too Chinese” for Dutch readers to understand, worrying that it might deter them or require excessive footnotes for explanation. However, these poems turned out to be truly fascinating, so perhaps I am mistaken in my usual approach to selecting works. Maybe I should put more effort into making such poems resonate in translation!

Too soon our week was over, and we all split up again… The breathtaking view looking out of the house, the comfort in the house, the easy-going atmosphere, the generosity of everybody present… The whole experience has led to a very productive week, in which we found a good balance between relaxing and working. Dylan Wang wrote a poem as a memento for this highly inspiring week in which he highlighted the things that we discussed. You can read it here:

At Home in Translation - Alice Grünfelder · literaturfelder

Many thanks to everyone involved, and special thanks to the incredibly supportive team at the Translators’ House Looren for accommodating us!

Editor's Note: The following consists of multilingual translations of poems by the Taiwan poet Ling Yu零雨, including〈木頭人〉,〈同樣的 〉,〈然後,然後—— 〉,〈翻譯——致A〉 ,〈松雪齋──致黃公望〉,〈看畫──歌川廣重《東海道五十三次》〉, and〈毛筆〉. The translations are crafted by a diverse group of scholars and translators during a Translation Workshop held at Looren in 2024, led by Silvia Marijnissen: Cosima Bruno (SOAS, University of London), Swiss-German writer, translator, and publisher Alice Grünfelder, Wen-chi Li (University of Oxford), Rosa Lombardi (Roma Tre University), Dutch translator Silvia Marijnissen, Silvia Schiavi (Roma Tre University), Yu-sheng Tsou (University of Munich), Dylan Wang (SOAS), Nicholas Y.H. Wong (The University of Hong Kong), and Tony Yu (National Taiwan Normal University).

〈木頭人〉零雨

一、二、三木頭人

我和我的小時候

玩著這個遊戲

一、二、三木頭人

我的母親──我和她玩

她躺在床上

我和瓦蒂一起扶她,坐起來

躺下來,翻身

和她說話

她不回答

也不點頭搖頭

還好眼睛會動,會看我

一、二、三木頭人

這個遊戲回來了

我和我的小時候

"Holzpuppe"

eins, zwei, drei – steif wie ‘n Stock

ich spiel mit mir als Kind

dieses Spiel

eins, zwei, drei - steif wie ‘n Stock

mit meiner Mutter spiel ich das Spiel

steif im Bett zu liegen

Wadi hilft mir, sie zu stützen, aufzurichten

hinzulegen, umzudrehen.

sprech ich mit ihr

antwortet sie nicht

nickt nicht, schüttelt nicht den Kopf

ihre Augen bewegen sich noch, sehen mich

ein, zwei, drei - steif wie ‘n Stock

das Spiel ist zurück

ich spiel mir mir als Kind

(Translated by Alice Grünfelder)

“Un, due, tre, stella!”

Un, due, tre, stella!

Io e la me bambina

facevamo questo gioco

Un, due, tre, stella!

Mia madre…gioco con lei

è distesa sul letto

Io e la badante la sosteniamo per sedersi,

sdraiarsi, girarsi

Le parliamo

non risponde

non abbassa né muove la testa

Per fortuna gli occhi si muovono, mi guardano

un, due, tre, stella!

Di nuovo quel gioco

io e la me bambina

(Translated by Silvia Schiavi)

"Stè là"

un, due, tre stè là

io e me da bimba

giocavamo così

un, due, tre stè là

io e mamma giochiamo

lei stesa sul letto

io e Vati l’aiutiamo, a sedersi,

stendersi, voltarsi

le parliamo

non risponde

nessun cenno col capo

ma i suoi occhi mi guardano

un, due, tre stè là

ancora quel gioco

io e me da bimba

Translator's note: The name of the game in Italian is “Un, due, tre, stella”. Originally, “stella” (star) was the phrase in Piemonte’s dialect stè là, which means “stay still there”. With time, stè là became stella.

(Translated by Cosima Bruno)

"Statues"

One, two, three, statue!

I and my childhood

Play this game together.

One, two, three, statue!

My mother—I play with her

While she lies in bed.

I and Vati together support her, help her up,

Lay her down, turn her over.

To my words,

She does not reply,

Nor does she nod or shake her head.

Fortunately, her eyes could still move and look at me.

One, two, three, statue!

This game has returned.

Me and my childhood.

(Translated by Dylan wang)

“Red Light, Green Light”

Green light, red light

Me and my childhood

playing this game

Green light, red light

My mother─I play with her

she is lying on the bed

Vati and I help her sit up

lie down, turn over

We talk to her

she does not answer

neither nod nor shake his head

Fortunately, the eyes can move and look at me

Green light, red light

This game starts again

Me and my childhood

(Translated by Wen-chi Li)

"Freeze"

Red light, green light

My youth and I

Played this game

Red light, green light

My mother—she and I play

She lies in bed

Wati and I help her sit up

Lie down, turn in bed

She does not reply

Our words

Nor does she nod or shake her head

Luckily her eyes can move, turn to me

Red light, green light

This game has made a comeback

My youth and I

(Translated by Nicholas Y.H. Wong)

"Fermi tutti"

Uno, due, tre, fermi tutti

io ed io piccola

mi diverto a questo gioco

uno, due, tre, fermi tutti

mia madre_____gioco con lei

giace a letto

io e Wati la facciamo sedere

distendere, girare

le parliamo

lei non risponde

non approva né disapprova

per fortuna può muovere gli occhi,

guardarmi

uno, due, tre, fermi tutti

ancora questo gioco

ed io ed io da piccolo

(Translated by Rosa Lombardi)

"Sei das Holz, Sei der Stein"

Eins, zwei, drei. Sei ein Holz.

Ich spiele mit meiner kindlichen Version Ich

dieses alte Spiel.

Eins, zwei, drei. Sei ein Stein.

Meine Mutter, auf einem Bett gestrandet.

Mit ihr spiel’s ich.

Die Vati und ich unterstützen sie, sich zu setzten,

zu legen, zu drehen.

Spreche ich zu ihr,

antwortet sie nicht,

nickt und schüttelt sie den Kopf nicht.

Zum Glück können sich die Augen noch bewegen,

mich verfolgend. Eins, zwei, drei.

Sei die sprachlose Natur.

Hier und jetzt ist dieses alte Spiel zurückgekehrt,

zusammen mit mir und meiner kindlichen Version Mir.

(Translated by Yu-sheng Tsou)

"annemaria koekoek"

annemaria koekoek

ik en ik als kind

in het spel dat ik speelde

annemaria koekoek

mijn moeder – ik speel met haar

ze ligt op bed

de hulp en ik helpen haar, zitten

liggen, omdraaien

praten tegen haar

ze antwoordt niet

ze knikt niet ja en schudt niet nee

gelukkig kan ze haar ogen bewegen, mij zien

annemaria koekoek

opnieuw dat spel

ik en ik als kind

(Translated by Silvia Marijnissen)

〈然後,然後—— 〉零雨

黑暗的樓梯。我好喜歡

那個黑暗。樓梯。通往大稻埕

繁華的宅邸

樓下擺滿宴席。我們在二樓

圓形廊柱間奔跑,一同指指點點

下面的客人,帶來歡樂、富貴氣象

僕役穿梭著,端出熱菜、湯圓、甜品

以及一些平時難得一見的精緻食物——

不是婚禮。該是因為戰後承平歲月

多出來的一份閒情。例如

一些節慶的藉口,或者輪流作東的

兄弟會。孩子們完全不理會這些

不明白戰爭(是什麼)。酬酢(是什麼)

節慶(是什麼)。只是高興。高興這麼多人

像為一齣大戲而演出。盛妝打扮。合宜的

禮貌。酒不停供應。食物從廚房無止盡出現

我們喜歡。從一樓掙脫大人的叫喊,跑上二樓

俯瞰樓下的鬧熱,然後繞著內室的露臺,再跑上

三樓。在那裡我們停下來。

我們看到那個黑暗的樓梯。

暗得好像藏了更多的熱鬧——

母親和姑婆,還有癡傻姑,她們在黑暗階梯上

坐著。說著小聲小聲的話

然後姑婆會流下眼淚,癡傻姑則楞楞笑著。然後

我們會迅速變安靜。偷偷坐一會兒。沒讓母親發現

然後我們假意躡手躡腳,又跳回樓下,不知誰帶頭爆笑開來

然後又在宴席中跑著追著。快速忘掉那個黑暗的樓梯

不久,姑婆和母親會出現

她們重新補妝,頭上插著紅花,再配上珍珠項鍊

笑容燦爛。滿座的人都笑容燦爛

然後,然後,誰還會留在那個黑暗的樓梯

"E poi, e poi…"

Scale buie. Quanto mi piaceva

quel buio. Scale. Una casa

lussuosa a Dadaocheng.

Al piano terra un grande banchetto. Al primo

noi corriamo tra le colonne, indichiamo insieme

gli ospiti di sotto, portano gioia e un’aria di fasto e ricchezza

Un viavai di domestici, piatti caldi, gnocchi di riso ripieni, dolci

e alcune prelibatezze che non si vedono spesso...

Non è un matrimonio. Deve essere un momento spensierato negli anni di pace

del dopoguerra. Forse

un pretesto per una cerimonia o un incontro periodico

tra amici. Ai bambini non interessa

Non capiscono la guerra (cos’è?). I brindisi (cosa sono?),

le celebrazioni (cosa sono?). Sono solo contenti. Contenti dei tanti ospiti,

sembra un gran spettacolo. Trucco e abiti eleganti. Buone maniere.

Fiumi di vino. Portate che arrivano di continuo dalla cucina

Ci piace. Via dalle voci dei grandi al pianterreno, saliamo al primo piano

per guardare la festa dall’alto, poi saliamo al secondo, costeggiando

la balaustra. Lì ci fermiamo.

Vediamo le scale buie.

Il buio sembra celare la vera festa…

Mia madre, la sorella del nonno e la zia svampita sedute al buio

sulle scale. Parlano a voce bassa

Poi la sorella del nonno piange, la zia svampita ride stordita. E poi

diventiamo di colpo silenziosi. Rimaniamo nascosti per un po’. E poi, senza che la mamma ci veda,

torniamo di sotto quasi in punta di piedi, qualcuno scoppia a ridere per primo,

e poi di nuovo al banchetto a correre e inseguirci. Dimentichiamo in fretta le scale buie

Poco dopo, appaiono la sorella del nonno e mia madre

si sono rifatte il trucco, hanno fiori rossi tra i capelli, collane di perle

e sorrisi radiosi. Tutti i presenti sorridono radiosi

E poi, poi, chi è rimasto su quelle scale buie?

(Translated by Silvia Schiavi)

〈同樣的 〉零雨

姊姊躺在醫院裡

她躺的姿勢和母親

一模一樣

我摩娑她的頭髮

她的手心,手背,胸部

像摩娑兩份人體

我問她今天有沒有好一點

也是一模一樣

同樣,沒有回答

同樣的眼神,同樣的

兩個骨架,同樣的鼻胃管

手背上的針筒

同樣,我的自言自語,不斷的

自言自語,像一個背著底稿的

說書人,只能自言自語

消除這裡的寂靜

(想必

奧秘,在那裡面——)

我離開醫院,同樣的

情緒澎派,同樣的

質問造物主——我總是

不斷質問,不斷和祂說話

同樣的,流下眼淚

——同樣的,沒有回答

我流眼淚,同樣的,惶惶然

回到家中,回到每天的書寫,同樣的

書寫,同樣的,沒有回答

(想必

奧秘,在那裡面——)

“Identical”

My sister lies in the hospital

the way like my mother

I caress her hair

her palms, the backs of her hands, her chest

as if I caress two bodies

I ask her if she feels better today

She does not answer

the way like my mother

Identical gaze, identical

skeleton, identical nasogastric tubes

syringes on the back of the hand

Similarly, my self-talk, constantly

talking to myself, like a storyteller

reciting what I can remember

murmuring to expel the silence

(Presumably

the mystery lies within—)

I leave the hospital, with identical emotion

questioning the Creator in the same way—

I always question

continually speak to him, shedding tears

Yet identical to before, he does not answer

I shed tears, with identical disquiet

Back home, back to my routine of writing

I write, but receive no answer

(Presumably

the mystery lies within—)

(Translated by Wen-chi Li)

〈翻譯——致A〉零雨

1

祖父回來了

他以A的樣子出現

A的容貌令我想起我的祖父

算算他的年齡,應在祖父死後十年出生

他能說流利的中文、英文、西班牙文

走遍亞洲、美洲、歐洲各國

精通這三種文化與文 學

我的祖父一輩子窩在偏僻的山村

除了土語,什麼語言也不會

就連土語,也不出那幾句

──他沉默寡言,難得開口

他去過的地方,最遠,就是走一小時

的山路,坐一小時的巴士,再走二十分鐘

到臺北──給我們帶來

各種土生土長的山產

2

我的祖父生病了,我替他翻背,倒尿袋

擦洗身體

那時我還太年輕,做得不夠好

而他消失得太快

他的消失

沒有讓我長大

我還是那麼天真幼稚

一想起他的臉

就流下眼淚

他的眼睛小小的,嘴唇厚厚的,臉龐瘦削

一派單純的農村風景

3

A就是以這樣的面貌出現

他看到我的淚水

──那些寫給祖父的詩句

他說,我來翻譯這些翻譯那些

淚水嗎,還是詩句

我猜想,應該是臉──

祖父和A的臉

互相翻譯

然後,我想我讀懂了

生命。一小部分的

奧祕

"Traduzione --- dedicato ad A"

1

Il nonno è tornato

con l’aspetto di A

L’aspetto di A mi ricorda mio nonno

calcolando l’età, deve esser nato dieci anni dopo la morte del nonno

parla bene cinese, inglese, spagnolo

ha viaggiato in Asia, America, Europa

conosce bene quelle tre lingue e culture

Mio nonno ha sempre vissuto in un remoto villaggio di montagna

eccetto il dialetto, non parlava altre lingue

e anche in dialetto, diceva solo qualche frase

…. era taciturno, apriva bocca di rado

Il posto più lontano dov’era stato, un’ora di cammino

tra i monti, un’ora d’autobus, e venti minuti a piedi

era Taipei…ci portava

i prodotti di montagna

2

Mio nonno si ammalò, io lo rigiravo, svuotavo la sacca dell’urina

lo lavavo

allora ero tanto giovane e inesperta

e lui se ne andò troppo in fretta

La sua scomparsa

mi impedì di crescere

sono ancora tanto ingenua e infantile

se ripenso al suo viso

piango

Gli occhi piccoli, le labbra piene, il viso magro

erano il vero ritratto della campagna

3

A è comparso con questo aspetto

nel vedere le mie lacrime

…quei versi dedicati al nonno

ha detto, tradurrò queste e quelli

le lacrime?, o i versi

immagino, il volto …

il volto del nonno e di A

uno traduce l’altro

in seguito, credo di aver compreso

la vita. Una piccola parte del suo

mistero

(Translated by Rosa Lombardi)

〈松雪齋──致黃公望〉零雨

這裡我們種下

幾棵松

雪下的時候

我們建造一個書齋

我們向這裡走來來

我是其中的最小的

一種偉岸的東西

在發光

被我們的筆秘密包裹著

只要我們一提筆

就洩露出點點光芒

(關於永恆的──)

中峰、側峰,焦墨、濕染

──世界漸漸形成

我們的世界──

在密林中

在層層的峰巒

在靠海的江邊

在幽深的竹篠裡

(把自己抽出,又置入──)

那獨行者的手杖是我

那崔嵬的樹幹是我

那岩石的縫隙,是我的

躲藏──

如此我虛虛實實

取景,描畫,且生活

在其中

如此我學到了一點:

我是且永是

松雪齋中小學生

"Lo Studio dei pini innevati--per Huang Gongwang"

Abbiamo piantato qui

alcuni pini

quando nevica

costruiamo uno studio

ci veniamo a piedi

io sono il più giovane

qualcosa di grandioso

risplende

avvolto nel segreto dei pennelli

nel dipingere i pennelli

sprigionano bagliori

(a proposito dell’eternità …)

tratti sottili, tratti forti, inchiostro denso, diluito

…il mondo poco a poco prende forma

il nostro mondo …

è nel profondo del bosco

è tra le cime dei monti

è sulle rive del mare

è nel fitto dei bambù

(ne esco, rientro …)

quel bastone da viandante sono io

quel tronco imponente sono io

quelle crepe nella roccia, sono il mio

rifugio…

così vivo tra realtà e fantasia

scelgo un paesaggio, lo dipingo, ci vivo

dentro

questo ho imparato:

sono e sarò sempre

un allievo dello Studio dei pini innevati

(Translated by Rosa Lombardi)

〈看畫──歌川廣重《東海道五十三次》〉零雨

4.(第33次)三盲女

我們被教導旅途的艱難

三個人,手搭著肩,他們說我們是三盲女

但我們看得見

三弦琴的琴弦顫抖,因著旅途的新鮮滋味

──樹葉的香,土地的寥遠

雄壯的琴音,讓弱者開懷

瘖弱的琴音,讓邪惡更強大

但那是他們的命運

我們是旁觀者

看得見旅途

在三個弦中轉彎,共振,互相聲援的

這種曲折

我們不好宣揚

是誰

安排我們

出現在這旅途最曲折處

像是被派遣來做困難作業的使者

"Looking at Pictures--Utagawa Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō"

4. 33rd Station, Three Blind Women

We are taught the journey’s hardship

Three people, propping their hands on shoulders, they said we are three blind women

But we could tell

The shamisen strings tremor from the journey’s fresh taste

—the fragrance of tree leaves, the far-flung nature of land

Their heroic tones bring succor to the weak

Their mute tones reinforce evil

But that’s their fate

We are bystanders

Able to see how the journey

Takes a turn in the three strings, those bends that resonate

In mutual support

We better not name

Who

Arranged for us

To show up at the journey’s most winding spot

Like envoys dispatched to perform unenviable tasks

(Translations by Nicholas Y. H. Wong)

〈毛筆〉零雨

我握住一枝毛筆

想賦予它靈魂

我將水注入小小硯池

我的意念旋轉

黑色降臨

祖傳的黑色

像黑壓壓的眾多祖父

從西元前列隊而來

小篆小轉

大篆大轉

金文有金屬聲

籀文有皺紋

我破筆刷出潑墨仙人

我工筆細描曹衣出水

他握住我的手

想賦予我靈魂

來一點黎明的飛白

雨天的迷茫

中午的明心見性

我溜進溜出。最後

在時光的隊伍中

我被辨認出來

──在最深沉的黑裡

"Penseel"

ik pak een penseel

om het te bezielen

ik giet water in de kleine inktsteen

mijn gedachten wervelen

zwart daalt neer

geërfd zwart

het ziet zwart van de voorvaderen

defilerend uit het begin der tijden

de kleine streken in klein zegelschrift

de grote streken in groot zegelschrift

de brons inscripties klinken brons

het zhou-schrift zit vol geestdrift

met een wijd penseel schets ik de onsterfelijke in waterige inkt

met een fijn penseel traceer ik de waterfee in natte zijde

het penseel pakt mijn hand

om mij te bezielen

vangt het vluchtig wit van ochtendgloren

de verlorenheid van regendagen

het ware hart op de middag

ik glij naar binnen en naar buiten. uiteindelijk

word ik in de parade van de tijd

geïdentificeerd

–– te midden van het allerdiepste zwart

(Translated by Silvia Marijnissen)