Taiwan Lit

Time Travel for Indigenous Futures: Sovereignty and Children’s Programming at Taiwan Indigenous Television

Kakudan Time Machine (Kakudan 時光機) is an award-winning children’s program produced by Taiwan Indigenous Television (TITV), the first Indigenously-run national television station in Asia.1Now in its fifth season, the show has received national recognition and won multiple Golden Bell Awards (Taiwan’s equivalent of the Emmy Awards in the United States) for Best Children’s Program and Best Host in a Children’s Program. Founded in 2005, TITV broadcasts news and cultural content created by and for Taiwan’s diverse Indigenous communities. Kakudan takes its name from an Indigenous Paiwan word meaning “cultural relations,” “cultural history,” and “customs” (Tang 2018). The program is designed for elementary and middle school-age children, with each half-hour episode centered on a specific topic. As a “time machine,” Kakudan foregrounds Indigenous cultural revitalization and continuity after centuries of colonial erasure, representing traditional knowledge on screen for the next generation. Like many TITV shows, it sets out to creatively decolonize television production and create a space for Indigenous media sovereignty: Indigenous self-representation and control over media production (Raheja 2007).

I got to know Kakudan through my anthropological doctoral fieldwork with TITV from 2019 to 2021. The show’s producer, Elreng Ladroluwan (恩樂‧拉儒亂, Rukai), generously invited me to join the production of Kakudan’s fourth season, including me in planning meetings and filming trips across Taiwan. Elreng is a veteran producer who brings over a decade of industry experience and a deep sense of commitment to her work, complemented by an infectious sense of camaraderie and curiosity. Episode shoots were both carefully coordinated and full of joy. Often the adults on set got just as caught up in the content as the children: one afternoon saw us pass our filming break breathlessly clustered around a microscope, immersed in a search for lac insects. Kakudan’s crew shared a passion for the content and a deep sense of care for younger generations, and Elreng always went out of her way to mentor the younger members of her team.

On screen, Kakudan reflects the team’s off-screen energy and experience, both in its dynamic scope of work – topics range from Tasabotu (Rukai women warriors) to hydropower and sustainable farming practices – and in the nuanced sensitivity the show brings to each topic. Audiences follow the program’s hosts as they travel throughout Taiwan and learn from a diverse group of elders and teachers, whose expertise interweaves oral history, cultural practices, local ecology, and material science. Each season is themed to elevate a different area of traditional knowledge, offering an Indigenous Taiwanese lens on archeology, cultural practices, and reusable resources. What I find particularly compelling about Kakudan is the way it integrates multiple forms of cultural and scientific knowledge, celebrating and asserting Taiwan’s diverse Indigenous epistemologies. Elreng and her team strike a careful balance throughout their work, narrating cultural complexities in ways that are accessible and engaging for young viewers.

In this essay, I work with Elreng to introduce Kakudan and offer an off-screen glimpse into the social dynamics of production: the complex ethical, aesthetic, and relational worlds that are embedded in each episode (Ginsburg 1994, 2018). We focus here on two episodes selected by Elreng to highlight different aspects of the show. For each episode we share a one-minute excerpt followed by two strands of commentary: one from Elreng’s perspective as the show’s producer (edited and translated from our conversations), and another from my perspective as an anthropologist. This approach allows us to center the visual medium, taking the episodes as our starting point for analysis. We also draw inspiration from the show itself, as we integrate complementary forms of knowledge through our different perspectives. Together, our aim is to demonstrate how Kakudan Indigenizes established frameworks of cultural and scientific expertise, recovers and revitalizes Indigenous knowledge, and asserts Indigenous media sovereignty for future generations.

Excerpt from Taimu Mountain Burial Culture, Part 2 (大武山下 墓葬文化)

Season 1, Episode 5 (2017)

Episode Summary: This episode offers an introduction to traditional Paiwan burial culture, in which ancestors are buried in the same home as their living descendants. Season host Lanpao (薛紀綱) travels to Nanke Archaeological Museum in Tainan and then to Kapiuman, a Paiwan village in Pingtung. In Kapiuman, Lanpao meets his two guides: Ipan, a young Paiwan teen involved in cultural revitalization, and Lavuras Kadrangian, a Paiwan author with expertise in traditional culture, oral history, architecture, and botany. Together they accompany an archeological expedition to a historic village site on nearby Taimu Mountain to excavate ancestral tombs.

Elreng:

Many people ask: why did we want to use traditional burial culture as a starting point for this episode? When we look to earlier periods in our history, it can be difficult to understand what life was like for our ancestors. By researching human remains, studying the styles of burial and kinds of objects our ancestors were interred with, we can start to understand the distinct practices and histories of Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples. This makes burial culture a particularly good entry point into learning about Indigenous culture more broadly. Through these sites, our audiences gain insight into Austronesian cultural systems and historical contexts. For instance, from the type of burial – where a body was buried and whether it was placed in a fetal or squatting position – we can identify what community a person was from. So, I selected this episode for this essay as an introduction, a way to help international friends who might not know much about Austronesian peoples to learn more about us.

In this episode, we filmed at the ancestral home and burial site of one of the most prominent families in Kapiuman village, the Wang Family. We conducted a long research process before filming and paid the family a formal visit to introduce our program and explain our goals for the episode. We always do this, no matter where or what we film. It is one of the most basic forms of respect. Because every tribe and every community has different cultural practices and prohibitions, we always meet with community leaders before each shoot to discuss our filming process and understand their boundaries. When we visit an old community site, are there any protocols to follow? Is there anything we need to be particularly attentive to? Are there any taboos we should avoid?

On the day we met with the Wang family in Kapiuman, the head of the family told us we would need to bring offerings to ancestral spirits inhabiting the burial site to inform them of our work and explain what we hoped to achieve. To do this we worked with the community’s shaman, a skilled practitioner who can communicate with ancestors in their own language. When we first arrived on the mountain, we lit a small fire, so the smoke would enter the area and let the ancestral spirits know that we had come to visit them – and you can see this in the episode. We prepared offerings of rice wine and betel nut and asked the shaman to explain our project to the ancestors and ask their permission to film. If the spirits agreed that we could film, they would let the shaman know. If not, then we would have had to leave and come up with another plan for the episode. Luckily, that day the ancestors liked us and allowed us to film.

It is also important to note that as media professionals we know how to film and express ideas on screen, but we’re not archeologists, and it was critical for us to work closely with archeological consultants throughout production. We were fortunate to partner with some of Taiwan’s leading experts in the field from National Taiwan University, and we couldn’t have made the episode without them. They brought a different perspective and type of scientific training, such as dating techniques to determine how long a body has been buried. In this way we were able to add another dimension to our story, so our audiences can benefit from non-Indigenous knowledge and culture as well as our Indigenous expertise.

Eliana:

When Elreng first explained to me that the first season of Kakudan was themed around archeology, I immediately wondered what this would look like. Since its emergence as an area of study in the 1990s, Indigenous archeology has been marked by nuanced theoretical debates over questions of power, knowledge, and accountability that are not easy to bring to life on screen (Atalay 2006). How could Kakudan represent the inherent contradictions involved in Indigenizing a historically colonial discipline? What would it look like to visualize complex questions of ethics and epistemology? And how would all this play out in the context of a children’s show?

Throughout the season, and particularly in this episode, Elreng and her team faced these challenges head on, with skillful scriptwriting and editing that assert Indigenous knowledge, cultural protocols, and authority. From the moment Lanpao (the non-Indigenous host for the season) arrives in Kapiuman village, his Paiwan host Lavuras takes the lead and establishes a framework for their collaboration. “I’ll bring you along,” he offers, “but there are conditions.” He explains that Lanpao must respect Paiwan customs and etiquette, which includes first asking permission from the Wang family, whose ancestors are interred at the burial site. The scene is short but significant. In just a few sentences Lavuras unsettles colonial notions of access and asserts Paiwan cultural protocols as a foundational part of archeological methodologies. Once Lanpao obtains the required consent, Lavuras guides him up Taimu Mountain along with Ipan and Kai-yen Chan (詹凱雁), a non-Indigenous archeologist from Nanke Archaeological Museum. Here again the episode upends colonial knowledge dynamics and asserts Indigenous expertise. Along the way, Lavuras pauses to introduce plants and explain aspects of traditional burial culture. These conversations are carefully edited to frame Lanpao and archeologist Kai-yen as students rather than experts, who pose questions that Lavuras answers with his extensive knowledge of ecology, material science, and cultural histories. Kakudan positions Lavuras as the primary knowledge holder, elevating Indigenous epistemologies on Indigenous lands.

As the episode draws audiences deeper into discourses of Indigenous archeology, questions of research motivations, methods, and ethics begin to converge. Standing at the edge of the excavation site, Lavuras explains that only those who share a bloodline with the deceased can excavate the burial. Furthermore, out of respect for the dead and in accordance with cultural restrictions, they will not open the tombs themselves. Ipan, Lanpao, and Kai-yen nod and look on, taking photographs and collecting data from the side while Kapiuman community members excavate the site. The scene is striking in the way it asserts Indigenous knowledge and authority, visually centering Indigenous relatives on screen while non-Indigenous guests stand to the side. With this framing, Kakudan challenges the distinction between “community member” and “archeologist” (Two Bears 2006), demonstrating how Kapiuman community members have cared for these burial sites for centuries, and will continue to do so. This moment also highlights differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous methodologies and asserts Paiwan authority to draw research boundaries. Archeology in Kakudan is not only a tool to understand a distant past; it is part of a living knowledge system that actively produces and shapes contemporary life. In Lavuras’ words: “If we don’t care for this place, the ancestors buried here will cease to exist, or they will just become history… I hope the young people with us today will return to care for these tombs and care for our ancestors, so that they will continue to watch over us.”

Excerpt from Searching for the Earth’s Colors (尋找大地的顏色)

Season 4, Episode 2 (2020)

Episode Summary: While most Kakudan episodes feature Indigenous communities, this episode offers a twist to the usual format. Host Lanpao travels to Caotun Township, where he meets HaoLun Hung (洪晧倫), a non-Indigenous painter and teacher who creates pigments from Taiwan’s natural resources. 1For images of HaoLun Hung’s work and additional news coverage, see his Facebook page: <a href="https://www.facebook.com/anghelun">https://www.facebook.com/anghelun</a>Joined by a group of Indigenous students, Lanpao and Teacher Hung collect soil and insect casings and use them to make their own pigments, learning about land conservation and natural resources along the way.

Eliana:

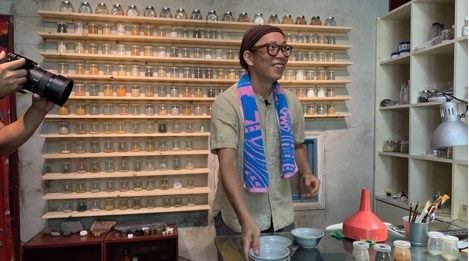

On a hot August afternoon, I stocked up on road-trip snacks at a 7-11 and joined the Kakudan team as they set out for Caotun, a densely populated township in Central Taiwan. As we pulled up at Teacher Hung’s workshop, I was excited and curious. Since Kakudan episodes were typically set in Indigenous communities, I wondered what it would be like to film in a different setting. How would this production experience compare with other episodes?

We started with Teacher Hung’s “pigment wall,” a display of pigments made from Taiwanese soil with rich, earth-toned hues that seemed to glow out of their glass jars. Teacher Hung walked us through the different pigments and introduced his research. His approach, he explained, was profoundly personal, “using Taiwan’s local colors to paint a connection between the land and self” (用台灣在地色,採製出土地與自己的連結). Over the next two days of filming, I observed how the Kakudan team approached production in a different way from other episodes, using strategic storytelling techniques to move through Teacher Hung’s work and approach Indigenous representation from a different angle. Elreng had written specific touchpoints into the script around Indigenous pigment use in Taiwan, interweaving these material histories throughout Teacher Hung’s introductions to his soil research and art practice. The episode also created a deep sense of place, with filming divided between the workshop, a nearby hill, and Teacher Hung’s orchard. We collected soil and insects, which were transformed into colors on screen, and longan fruits, which we enjoyed behind the camera. The narrative thread here was subtle but strong, using pigments and art practice to reimagine the relationships between land and self. Elreng and her team moved through pigments and their production processes to open new pathways of connection between people and place, and to celebrate Taiwan’s uniqueness, as a small island that produces an abundance of color.

Looking beyond this episode, the production dynamics in Caotun reflected a broader ethic of collaboration at TITV between Indigenous and non-Indigenous experts, from the guests featured on screen to the wide range of media professionals who join production. Kakudan’s production team partnered with a non-Indigenous freelance director and camera crew, a common arrangement for many TITV programs. When I expressed surprise at this, Elreng explained that these collaborations can be highly generative. Non-Indigenous directors or partners, like Teacher Hung or host Lanpao, approach Indigenous representation from a different starting point, and so bring useful perspectives to a shoot. They can also serve as proxies for a non-Indigenous audience, identifying topics that mainstream viewers may find particularly interesting or require additional context to understand. As Kakudan negotiates different audience imaginaries – seeking to both inspire young Indigenous audiences and connect with non-Indigenous viewers – creating space for different perspectives becomes an important part of the production process.

What I find particularly important here is the way relationships of production at TITV are structured around Indigenous leadership and expertise. In this episode, Elreng and her team carefully managed each stage of production, even when embracing different forms of collaboration. During the planning stages, they selected the episode’s topic and situated it within the season’s theme of reusable resources. In pre-production they conducted in-depth research into Indigenous pigment use, consulted Teacher Hung, crafted the episode’s narrative, and wrote the script that would guide filming. During the shoot they managed workflows and attended to small details that the non-Indigenous crew had overlooked, ensuring, for instance, that the guest students used their Indigenous names in addition to their Chinese names. And in post-production Elreng and her team guided editing, added additional context and details, and approved the final cut. Taken together, these stages reflect TITV’s approach to decolonizing production and establishing Indigenous media sovereignty, creating space for Indigenous self-representation within Taiwan’s mainstream media world. This opens new possibilities for representation and gives producers like Elreng the space to experiment with formats and narrative techniques, innovating new ways to represent Indigenous cultures and knowledge on screen.

Elreng:

Historically, Taiwan’s Indigenous clothing lacked color. There were no pre-made pigments, and people had yet to research or invent the many colors we have today. But our ancestors were able to find color in their lives, using natural resources like plants, minerals, and insects to create many beautiful hues. Our ancestors figured out how to use yams to create purple and red dyes, ground shells for white, and the soot that forms on the bottom of cooking pots for black. Because charcoal was burned at such a high heat, the soot it produced had very few impurities, and so was also used in traditional tattooing. I selected this topic because I wanted to show how much knowledge our ancestors held. Through this, I also wanted to teach young people about the ways our chemical use impacts our environment. The synthetic colors in our clothes today are full of chemicals, and when we wash our clothes, some of the chemicals come off and gradually pollute our rivers. With this topic, we wanted to show our audiences that there’s an alternative. We don't have to destroy the environment with chemical dyes, because our earth is already full of colors that make our life rich and vibrant. Our ancestors have shown us this is possible.

In this episode we decided to work with Teacher Hung because he is one of the leading experts in Taiwan conducting this kind of soil research. He also has a lot of experience working with children, so he is able to explain complex concepts in a way that our young audiences can understand, which is very important. While our focus is on revitalizing Indigenous knowledge, we don’t restrict the experts in our show to Indigenous guests or scholars. All of our lives are on this island, and together with the many different communities here we make up a multicultural, multiethnic place. There are many different kinds of knowledge in Taiwan, each valuable in their own way, and we hope our children can learn from them all. With the pigments, for instance, we wanted to teach our audiences that even though Taiwan is a small island, we can find 11 out of the 12 global categories of soil here. This means that Taiwan has more colors than any other island in the world. This kind of knowledge is not taught in school, and our goal is to use television to broadcast these insights across Taiwan. Here I want to emphasize that our program is not only for Indigenous audiences. We are in the middle of filming our fifth season, and we have many non-Indigenous children joining us as guests. We hope to create an open educational environment to share many kinds of knowledge, where children from different backgrounds can learn together and gain mutual appreciation and understanding.

This brings me to why I created Kakudan. The name comes from a Paiwan word that means “cultural relationships and practices.” My inspiration came from my grandmother, who is 96 years old now. I always loved to hear her tell stories from earlier times, and one day she asked me, “Why do you always listen, but never film me?” She told me I should use film to record our community and her memories; otherwise, she would pass on and all the stories she carried would be lost. The idea for the episode about burial practices came from her: I asked if she had any ideas for topics, and she suggested I start with our Rukai burial tradition of interring the dead beneath the home, so that we live alongside our ancestors. So, I am making this program and learning at the same time. If we do not record our elders now, we will not have any way to teach the next generations of children how our ancestors lived on this land. There is a lot of knowledge to bring back, and it is difficult work, but we will keep moving forward. I am happy I can teach my own children about our culture, and honored to work to bring back our histories piece by piece.

然而處於文化逐漸式微的困境,又面對長者生命的迅速凋零,我們如何搶救文化?如何教育下一代有正確的文化知識與視野?如何把傳統說得更清楚?這就是節目製播的最大重點。1The mission statements for each of <em>Kakudan</em>’s seasons can be found on the show’s home page: <a href="https://www.ipcf.org.tw/zh-TW/Program/Program_Detail?programID=21081906450309567&categoryID=21061611343135413">https://www.ipcf.org.tw/zh-TW/Program/Program_Detail?programID=21081906450309567&categoryID=21061611343135413</a>

In the context of profound cultural loss, amplified by the passing of so many elders, how can we bring back our cultural heritage? How do we educate the next generation so they have accurate cultural knowledge and understanding? How can we make our traditions clearer? These are the goals of our program.

The episodes introduced here are just two of many, but we hope they offer a glimpse into Kakudan and the dynamic social worlds of its production. Now in its fifth season, Kakudan has covered a range of topics and traveled with its audiences across Taiwan, from the ancestral burial site on Taimu Mountain to, most recently, a youth boxing club in New Taipei City. The questions above reflect the show’s “time machine” concept, traveling back through time in order to move forward. Episodes share a thematic emphasis on ancestral connections and intergenerational knowledge transmission, and on finding creative ways to elevate Indigenous elders and teachers – as with Lavuras and traditional Paiwan burial practices. Additional forms of expertise are also valued and included, but they are always positioned within Indigenous knowledge frameworks. It is in this way that Kakudan plays a critical role in Indigenizing both media and knowledge production: the show generates knowledge systems that center Indigenous epistemologies and expertise, and brings them to life on screen. This in turn opens up possibilities for cultural revitalization and transmission, representing Indigenous knowledge on Indigenous terms for the next generation.

As a project of sovereign self-representation, children’s shows like Kakudan are particularly important in the context of Taiwan’s national mediascape, where mainstream media largely overlook Indigeneity or revert to stereotypes (Sterk 2014, Lin 2015). This was reflected painfully during the 2020 Golden Bell Awards, when Kakudan’s hosts Si Pangoyod (Tau) and Buya Watan (Atayal) won Best Children’s Show Host, and wore their traditional clothing onstage to accept the award. It was a powerful moment, and the young men’s pride is palpable through the screen.1Si Pangoyod and Buya Watan’s full acceptance speech can be viewed here: <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuHKYJAXZ5c">https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuHKYJAXZ5c</a>However, in the flurry of news reports that followed, Taiwan’s mainstream media attacked Pangoyod for his “overly exposing” traditional Indigenous clothing. While Pangoyod received overwhelming support from TITV and Taiwan’s Indigenous community, and later Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture, media incidents like this reinforce the critical role TITV plays in creating safe, sovereign spaces for Indigenous self-representation – particularly for the next generation of viewers. As a children’s program, Kakudan mediates Indigeneity for young Taiwanese audience, using television to make powerful claims for the significance of traditional value systems, contemporary presence, and sovereign futures.

Reference

Atalay, Sonya. 2006. “Indigenous Archaeology as a Decolonizing Practice.” American Indian Quarterly, Summer (30) 3/4.

Ginsburg, Faye. 1994. “Embedded Aesthetics: Creating a Discursive Space for Indigenous Media.” Cultural Anthropology 9 (3): 365–82.

———. 2018. “Decolonizing Documentary On-Screen and Off: Sensory Ethnography and the Aesthetics of Accountability.” Film Quarterly 72 (1): 39–49.

Lin, C. 2015. “Aborigines and Disasters: The Plight of the Aborigines Overlooked by the TV Media during Typhoon Morakot in Taiwan.” China Media Research 11 (3): 21–30.

Raheja, Michelle. 2007. “Reading Nanook’s Smile: Visual Sovereignty, Indigenous Revisions of Ethnography, and ‘Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner).’” American Quarterly 59 (4): 1159–85.

Sterk, Darryl. 2014. “Ironic Indigenous Primitivism: Taiwan’s First ‘Native Feature’ in an Era of Ethnic Tourism.” Journal of Chinese Cinemas 8 (3): 209–25.

Tang, Zuxiang (唐祖湘). 2018. “Kakudan 搭乘Kakudan時光機回到部落體驗傳統文化 [Take Kakudan time machine to experience traditional tribal culture].” Indigenous Sight 22. http://ipcf.org.tw/uploadEbook...

Two Bears, Davina. 2006. “Navajo Archaeologist Is Not an Oxymoron: A Tribal Archaeologist's Experience.” American Indian Quarterly, Summer (30) 3/4.

Video Sources

Searching for the Earth’s Colors (尋找大地的顏色), created by Elreng Ladroluwan, Season 4, Episode 2, Taiwan Indigenous Television, 2020.

Taimu Mountain Burial Culture, Part 2 (大武山下 墓葬文化), created by Elreng Ladroluwan, Season 1, Episode 5, Taiwan Indigenous Television, 2017.

【金鐘55】兒童少年節目主持人獎,得獎人《Buya陳宇、Pangoyod鍾家駿/kakudan時光機》!! YouTube, uploaded by Golden Bell Awards, 26 Sep. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuHKYJAXZ5c.

Full-length versions of all Kakudan episodes are available on the show’s homepage at the Indigenous Peoples Cultural Foundation website: https://www.ipcf.org.tw/zh-TW/Program/Program_Detail?programID=21081906450309567&categoryID=21061611343135413